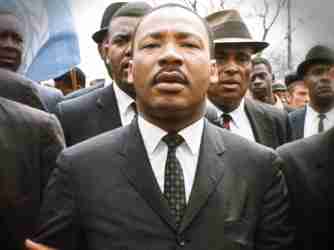

Fifty years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., American perceptions of progress toward racial equality remain largely divided.

PHOTO COURTESY OF HISTORY.COM

By MAUREEN LINKE and ANGELIKI KASTANIS

Associated Press

Fifty years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., American perceptions of progress toward racial equality remain largely divided along racial lines, a recent AP-NORC poll shows . The majority of African-Americans surveyed saw little to no progress toward equal treatment in key areas that the civil rights movement sought to address. White respondents frequently portrayed a rosier picture. A review by the Associated Press shows that the available data more often align with African-Americans’ less optimistic reflection of their reality.

The survey asked respondents how African-Americans have fared in topics ranging from access to affordable housing to political representation. Three topics generated the most polarized responses from African-Americans and whites: treatment by police, the criminal justice system and voting rights.

TREATMENT BY POLICE

King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech set police brutality among the chief issues civil rights activists sought to address. Poll responses show that more than 7 out of 10 African-Americans think little or no progress has been made in treatment by police over the last 50 years.

Assessing any change in police treatment of African-Americans isn’t easy because comprehensive data on police interactions and use of force is difficult to obtain, especially in a historical context. However, several studies have attempted to use federal surveys, state administrative data from traffic stops, and FBI arrest data to gauge the scope of the racial disparities. Their findings indicate sustained inequality in this area.

Traffic stops are the main reason police interact with the public, and some studies indicate that the experiences of white and black drivers are remarkably different. A Stanford University study pieced together data from 16 states to show that black drivers are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, searched and arrested than white drivers. Another study by a professor at Harvard University compiled data from federal sources and concluded that when black drivers are stopped by police, they are more likely to be grabbed, handcuffed and have a gun pointed at them than white drivers.

Similar data from police interactions in the 1960s and 1970s aren’t available for comparison.

CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

At the time of King’s assassination, the U.S. prison population was a fraction of its current size, and the rate of incarceration for African-Americans was more than five times the rate for whites, data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show. In the AP/NORC poll, more than 6 of 10 African-Americans said that little or no progress has been made in the criminal justice system’s treatment of African-Americans in the last 50 years.

By the late 1990s, the rate of black incarceration had risen to over eight times the rate for whites. While that gap has narrowed, data from BJS shows that in 2016 it still remained slightly wider than it was in 1968.

The criminal justice system’s disproportionate impact on the African American community goes beyond the incarceration rate. African-Americans make up around 12 percent of the U.S.

population but account for 38 percent of the population on parole, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics . Of the 3.8 million Americans on probation, nearly a third is African-American. Violating probation terms can result in a longer probation period or further incarceration, and according to a study by the Urban Institute , blacks are significantly more likely to have their probation revoked than whites.

VOTING RIGHTS

In his “Give Us the Ballot” speech in 1957, King fiercely called for equal voting rights and emphasized the importance of participation in civic life. In the AP/NORC poll, voting rights was the issue given the most positive response: 63 percent of blacks and nearly 90 percent of whites indicated at least some progress. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 aimed to protect African-Americans from widespread discriminatory practices, and voter registration trended upward shortly after. But critics say new obstacles _ such as voter identification laws and regulations for those with felony convictions _ limited those rights over the years.

No Comment