By ISHEKA N. HARRISON

iharrison@sfltimes.com

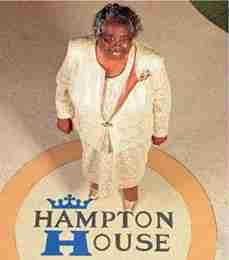

Dr. Enid C. Pinkney may be small in stature, but she is mighty in spirit. The 85-year-old dynamo is one of Miami’s most notable living treasures. Pinkney has spent her life fighting for justice, equality and the preservation of black history.

Whether working to integrate Miami when it was considered illegal or fighting to ensure the city’s black history is not forgotten, Pinkney has embodied King’s dream by fighting for justice and equality.

Born in 1931 in Historic Overtown, Pinkney is the third of Lenora and Henry Curtis’ four children. She became a leader early in life, participating in sympathy marches designed to express disdain of how blacks were treated across the country.

“We would march down Third Avenue with all the leaders and ministers of Miami,” Pinkney said. “One time a woman had gotten killed in Mississippi and we marched to show our hostility and resentment about it. I remember those marches.”

As a teenager and young adult, Pinkney had many experiences that shaped her worldview. Among them was being banned from eating because she and her classmates were black at two separate conferences she attended in high school and college, respectively.

As a student at Booker T. Washington (BTW) High School, Pinkney said her principal and teachers wanted to expose them to wonderful opportunities; one of which was attending a “Chain of Missions” conference at the Miami Women’s Club.

“The leaders of that conference said they didn’t mind us coming but they told our principal we couldn’t eat because segregation laws said we couldn’t eat with the white children,” Pinkney recalled.

She and her peers had to walk back and forth several times from what is now the

Bayshore area where the club is located to Overtown just to ensure they ate. But Pinkney did not just take that, or any other, injustice lying down.

She worked at integration, serving as a treasurer of the Christian Youth Council, the president of BTW’s student council and the first black president of Natives of Dade, an integrated group for people who were born and raised in Miami.

While attending Talladega College, in a completely different state, Pinkney said she had Déjà vu.

“There was a conference taking place in Birmingham, which was about an hour away. We wanted to attend the conference and the same thing happened,” Pinkney recalled. “They said we couldn’t eat so we decided to fast. After realizing we weren’t eating, some of the white students said if we couldn’t eat, they wouldn’t either. They joined the fast.”

These and other experiences influenced Pinkney, however, she credits her father’s example as being most impactful.

“My father was a minister from the Bahamas and I watched him stand against things,” Pinkney said. She recalled a specific time when her father was slapped in his face by a policeman for refusing to take off his hat after being stopped for having on his bright lights.

“My father didn’t know he had on his bright lights. But he was an expert on the constitution because he went to school at Dunbar to pass the citizenship test. He knew his rights. When the officer told him to take off his hat, he asked, what law am I violating by keeping my hat on,” Pinkney said.

After being slapped, Pinkney said the policeman ordered her father to apologize and arrested him for insubordination when he refused – leaving Pinkney, her mother and brother stranded on State Road 9.

“My father told the officer, I’m not going to apologize to you for slapping me and knocking my hat off … I’m going to be the last black man you slap because I’m calling my boss.”

According to Pinkney, the officer ended up bringing her father back to their car and letting him go that same evening because he worked for a very high profile man; but the experience forever shaped her.

“I witnessed all of that and I feel if my father, who had an eighth grade education, could stand for principles and stand for what’s right, I owed it to everybody to do what I can to make things better for everybody,” Pinkney said.

She has done just that. Throughout her life, Pinkney has worked as a social worker, educator, historian and preservationist. She was elected the first black president of the Dade Heritage Trust in 1998, where she founded the African American Committee, which focuses on the contributions of blacks to the community.

She was also instrumental in founding the Historic Hampton House Community Trust to have the former Brownsville Hotel – where greats like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis and Althea Gibson stayed when they came to Miami – designated as a historic landmark.

Pinkney was also one of the driving forces behind halting an affordable housing development that was being built on the forgotten Lemon City Cemetery, where many of Miami’s black pioneers were buried. Today it is a historic site with a marker listing those for whom it was a final resting place.

Today Pinkney still serves at the Hampton House daily, working to make sure black history and the contributions blacks have made to Miami are not lost. She believes it is critical that accurate stories are passed down to future generations.

“One of the problems that we have as a people is that we don’t’ cherish who we are and we don’t really celebrate our history and pass it on to the generation that’s coming along,” Pinkney said. “We have to get the young people to understand their own history, their family history and know that they are from great people and communities that deserve respect. The foundation that has been built for them needs to be perpetuated by them and they need to learn about it.”

To help accomplish this, the Hampton House is working to offer programs in music, history and archiving. Pinkney said they cannot be successful without the help of the community.

“What I really want to do is hand this over to a younger generation. I’m hoping they will come aboard and learn what it’s going to take to keep it alive,’ she said. “It’s an expensive place to maintain. We need people to use the building, to volunteer to teach. For sustainability what we need is the cooperation of the community.”

Summarily, no one has to tell Pinkney how important it is to be the dream because she has lived by the sentiment her entire life.

“The experiences that I’ve had propelled me to want to stand up for what is right,” Pinkney said. “I lived through segregation and came into integration and I just believe when you know your foundation and know from whence you come, you build your self concept. I want our youth to build their self-concept so they respect themselves and try to achieve higher goals.”

No Comment