JACKSON, Miss. (AP) – If you’re looking for a ticket out of Mississippi, earning recognition as a New York Times bestselling author is a good start.

That descriptor will take you places, especially when your debut novel has been on that bestseller list for more than 80 weeks and has been adapted for the big screen.

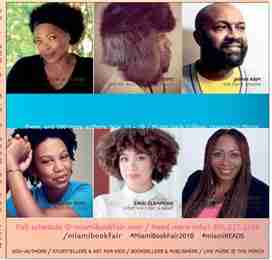

“The Hate U Give” author Angie Thomas still calls Mississippi home.

Not home as in the place that the 30-year-old returns to for holidays and select speaking engagements but home as in “sorry that you can hear our landline ringing in the background” while she’s doing this interview from her home in Jackson.

“Everything is just really surreal,” said Thomas, a 2011 graduate of Belhaven University in Jackson. “It’s been a crazy year. It’s been amazing just to see how far this book has gone. I’m starting to get a glimpse of how much further it can go.” Released in 2017, Thomas’ novel centers on Starr, a black teenager who witnesses a police officer shooting her childhood friend. It’s a coming-of-age story – complete with the after-school job at the family store, fallouts with best friends and teenage romance – that intersects with a social justice message.

“I think my big goal was for kids who are like Starr to see themselves in the character and see how amazing they are,” Thomas said. “I want them to see they have a voice and know the power of that voice.” It’s a timely theme.

The idea of who has a voice, how Americans should use their voices and perhaps most critically which voices should be listened to is fueling some of the most heated political conversations today.

Thomas views her book as a starting point for dialogue.

Five months after a rally of affiliated hate groups in Charlottesville, Virginia, ended in the death of a counter-protester, several high schools in the area partnered in asking students to read the book as a bid to move forward.

Thomas has also heard from educators who hosted classroom book clubs and invited police officers to read the novel and participate. She holds a firm belief that books can be “mirrors, windows and sliding doors.” Thomas recalled receiving an email from a reader who described herself as a middle-aged white woman in rural Alabama. The writer told

Thomas her father was an ardent white supremacist. The woman wrote of being instilled with the idea that black people were inferior and of holding the beliefs herself.

“As she got older she struggled with it and started to come into her own,” Thomas said. “She’s slowly but surely reforming herself and someone told her she should read my book.” Thomas acknowledges being taken aback by the confession.

“Part of me was like, wait – you didn’t see us as human,” she said, but Thomas embraced the reader’s admission as an illustration of “the power of literature” and as one step on the rung to fostering better race relations.

The warm reception of her book in her native state has at times challenged the author’s own tug-of-war relationship with Mississippi.

Critics have been eager to brush off Thomas’ book as anti-cop, despite the fact that Starr’s uncle, who serves as a surrogate father figure in Starr’s life, is a cop.

Yet there was Republican Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, a champion of the state’s “Blue Lives Matter” law, recognizing her at the 2017 Mississippi Book Festival for showing young Mississippians that they “can reach their dreams.”

No Comment