By LINDSEY BAHR

AP Film Writer

Would you stand by your child if she was slowly dying of a gruesome and highly contagious illness? That’s the central question that Arnold Schwarzenegger has to face in Maggie, a terminal illness drama where the malady at hand involves morphing into a member of the flesh-eating undead.

Director Henry Hobson’s film imagines a world devastated by zombies — although no one ever says that word. Instead of turning to genre conventions, though, Maggie stays small, intimate, and fascinatingly realistic.

Set in a small Midwestern town, society is still tenuously functioning amid the breakout. Hospitals diagnose the afflicted and set terms for mandatory quarantines before the diseased turn truly dangerous. The police, also, are there to enforce. Other institutions, though, are all but abandoned. Gas stations are empty and electricity is unreliable.

For many, life continues as normally as possible. There are no rogue bands of hostile survivalists competing over bunkers and land and no massive zombie armies attacking. Maggie is zombie tale that is more interested in the microcosm — the effects of the virus on the family unit and the community, not the shocks and thrills of an all-out war.

If this seems like a surprising choice for Schwarzenegger, it is. Even more surprising? He’s pretty great.

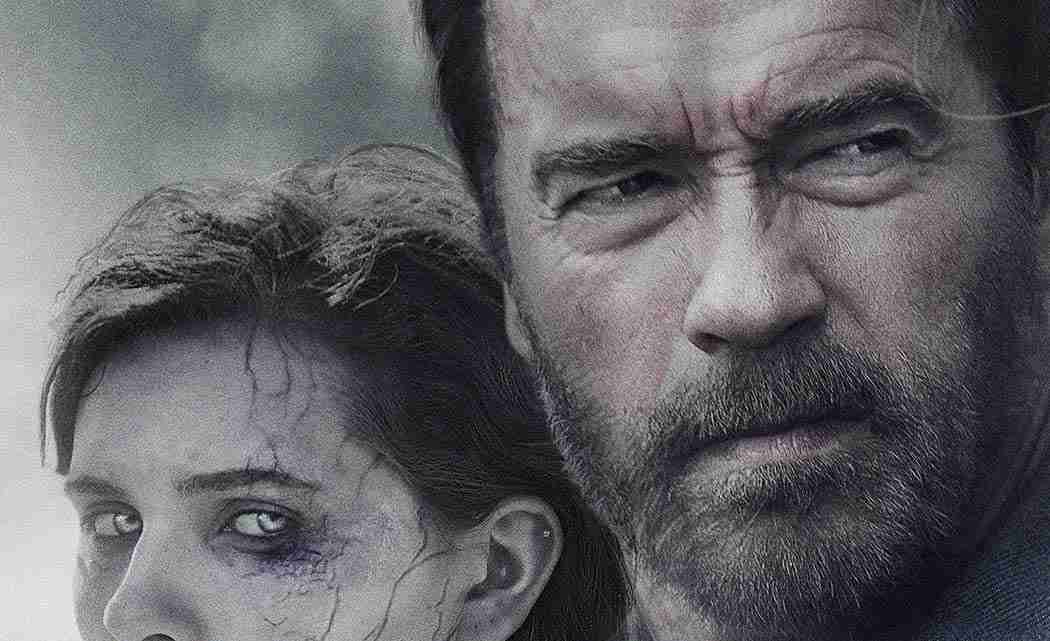

The heart of the movie is the relationship between Wade (Schwarzenegger) and his teenage daughter Maggie (Abigail Breslin). She’s infected and missing when the film starts, but Wade searches for two weeks to find her and bring her back to the country home that he shares with his new wife (Joely Richardson) and their young children.

There, Wade waits for Maggie to transform, trying to spend as much time with her as possible in the interim. Maggie, in turn, fluctuates between all the emotions of dealing with a life cut too short — and her fatal, itchy and grotesque wound.

There are a few jump scares and horror movie elements that help to break up the melodrama. Maggie’s carefully designed physical transformation is punctuated by frightening visions of what’s to come — even if it’s unclear whether they’re nightmares or symptoms.

Still, everything is restrained. Schwarzenegger’s Wade only resorts to violence when protecting Maggie, and even those moments seem to be done reluctantly. His despair is evident in his physicality and his eyes throughout.

Many of the scenes take place around the dinner table — some tense, some funny, but all with the heavy fear of the inevitable hanging over every moment.

Some of the more affecting parts involve Schwarzenegger weighing his options with various friends. The horrifying reality is that death is really the only solution. The “how” is the question.

And yet, for as fascinating as the conceit is (and as lean as the movie is), the deep emotions at play don’t really hit as well as they should. Part of the problem is the distracting look of the film. Maggie appears as though it was shot through a variety of Instagram filters — a dusty grey for the exteriors, and a warm, oversaturated orange for the interiors. Also, even at a brisk 95 minutes, the runtime feels like a stretch.

Maybe Hobson — a title designer in his feature debut — wasn’t going for tearjerker, though.

Maggie, ultimately, is a fascinating experiment in genre that has captured a side of Schwarzenegger that the movies have not seen before — an impressive, exciting and worthy accomplishment in and of itself.

No Comment