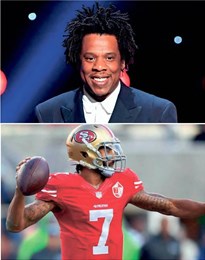

Three years after National Football League quarterback Colin Kaepernick protested social injustice by first sitting and later kneeling for the national anthem, the NFL signed a contract – with music mogul Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter.

None of the NFL’s 32 teams was willing to hire Kaepernick. Instead, the League signed Jay-Z and his Roc Nation in August to collaborate on “social justice initiatives” and on Super Bowl half-time shows, making him its “live music entertainment strategist.” The deal also includes an “Inspire Change” initiative, which includes a Players Coalition, to promote “economic empowerment, police and community relations and criminal justice reform.” A music showcase, Songs of the Season, debuted on Sept. 5. Some reports say that Jay-Z, a billionaire, could become the first African American part-owner of an NFL team.

“I think we’ve moved past kneeling,” Jay-Z told reporters. “I think it’s time to go on to actionable items.” Many commentators, however, accused him of selling out to the enemy.

Comedian, writer and activist Kerry Coddett wrote in The Washington Post that Jay-Z set Kaepernick’s “social movement… back and cost it its solidarity.” Carolina Panthers safety Eric Reid, a staunch Kaepernick ally, accused Jay-Z of “knowingly” making “a money move with the very people who have committed an injustice against Colin and is using social justice to smooth it over with the black community.” Michael Carmichael wrote on the National Public Radio website that “the whole thing has played out like a tragic blaxploitation flick.”

But Georgetown University sociology professor Michael Eric Dyson countered in a Washington Post column, “Jay did not write off protest when he said we are ‘past kneeling.’ He simply cast Kaepernick as a runner in a relay race rather than a boxer fighting alone in the ring.” The accord, he added, “represents a valid and potentially viable attempt to raise awareness or injustice to black folk and to inspire the League to embrace just action for the black masses. It may fail – and it certainly should not be used to diminish Kaepernick’s noble, iconic battle – but the effort is not a repudiation of justice. It is an attempt to make justice real for black folk far beyond the elite circles in which Jay and Kaepernick travel.”

The Players Association, which represents the 1,696 NFL players, 70 percent of whom are African American, could have staged a boycott until Kaepernick was hired. Instead, players struck a deal with the League in which the NFL will donate $89 million over seven years to tackle, Dyson said, “racial and social inequality where they thought they could make the biggest impact, including police and community relations, criminal justice reform and educational and economic advancement.”

For his part, Jay-Z has promoted social justice, generally, long before Kaepernick started his protest. As Dyson noted, Jay-Z “has advocated for social justice in his music and beyond the stage for more than two decades – by writing op-eds and creating an organization to lobby for criminal justice reform; by bailing out Black Lives Matter protesters; by supplying legal help for black victims of racism; by creating documentaries about victims like Trayvon Martin and Kalief Browder; and by speaking about police brutality and racial injustice.”

Meanwhile, Kaepernick’s campaign has continued to attract support and opposition. Most recently, Race Imboden, an Olympic medalist fencer and member of the men’s foil team that won gold at the Pan American Games, knelt on the podium during the national anthem and medal ceremony on Aug. 9 at the Pan American Games in Lima, Peru. Hammer-thrower Gwen Berry raised a fist and bowed her head during the same ceremony. Both were reprimanded and put on 12-month probation. Alissa Perry, a math teacher at Port Charlotte High School, created a tribute to Kaepernick during Black History Month – but was forced to take it down..

The mistaken perception that Kaepernick has insulted the national anthem persists. But, a year before he began kneeling, he and his partner Nessa started “Know Your Rights” camps to teach youths that they have rights: to be free, healthy, brilliant, safe, loved, courageous, alive, trusted and to know their rights. The fifth camp, held at The Historic Lyric Theater in Miami’s Overtown neighborhood on Oct. 27, attracted more than 250 youths.

Kaepernick has said that he started kneeling after the 2015 killing of Mario Woods, whom San Francisco police officers shot 21 times, including six times in the back, as he held a knife, TMZ reported. Police claimed Woods threatened them with a knife but cellphone footage showed him holding the knife at his side. But social justice has always been Kaepernick’s goal. After Harvard University awarded him its W.E.B. Du Bois medal, reserved for those who have “made significant contributions to African and African-American history and culture” and “individuals who advocate for intercultural understanding and human rights,” he talked in his acceptance speech about meeting members of an Oakland, Calif., high school football team. One of them told him, “’We don’t get to eat at home, so we’re going to eat on this field.’ That moment has never left me. And I’ve carried that everywhere I went.”

No Comment