photo courtesy of theshadowleague.com

On August 28, 1986, in the foothills of Alabama, in a town called Rome Georgia police found Queen Madge White dead on the floor of her home. The 79 year old widow had been brutally beaten, raped and murdered. Her home had been burglarized. Timothy Tyrone Foster, 18 at the time of the crime, was arrested after his girlfriend informed the police that “he was involved in the crime and had given her several items taken from the White home.”

However, as the prosecution’s investigator testified later, “no one can carry an air conditioner as big as he had took out of that window…and carried it home. He couldn’t have done it by himself.” ” It was not clear how many people were involved or what role precisely Foster, who had an I. Q. of 50 to 80 actually played.

The issue in foster’s case centers on the selection of the jury.

Jury selection has two phases. In the first phase called voir dire both sides question the jurors and eliminate those who show evidence of bias. These jurors may be struck from the jury “for cause.” The first phase whittled the jury down to 42 qualified citizens.

In the second phase known as “striking the jury,” both sides have an opportunity to use peremptory strikes. Because these peremptory challenges allow prosecutors to remove a juror on a whim. They provide potentially a cloak for racism, conscious or unconscious. The prosecution had ten of these challenges- Foster had twenty.

The morning of the second phase one of the five black jurors in the jury pool, Shirley Powell, stated she had learned that one of her close friends was related to Foster. She was removed “for cause.” The prosecution then used four of its strikes to eliminate all of the remaining qualified black prospective jurors.

The all white jury that resulted in foster’s case convicted Foster of murder.

The prosecutor then urged the jury to impose a death sentence to “deter other people out there in the projects. “ Ninety percent of those in the local housing projects were black. In May of 1987 foster was sentenced to death.

The year before Foster was sentenced the Supreme Court decided in a landmark case called Batson v Kentucky that the exclusion of jurors on account of race violates the Fourteenth Amendment equal protection clause.

Foster’s lawyers objected at trial to the striking the black jurors on Batson grounds. The court did require the prosecutor to explain his use of peremptory strikes. Stephen Lanier the prosecutor argued that he was motivated entirely by race neutral factors. He argued for example “three of the four blacks jurors in question were women, and he did not want women on the jury because women had “serious reservations” when the death penalty was involved.”

The court accepted the explanations as reasonable.

Despite their claim of color-blindness the prosecution’s notes showed otherwise.

While jurors were being picked, prosecutors had highlighted the names of African Americans, circled the word “black” on questionnaires, and added notations such as “B#1” and “B#2.” On a sheet labeled “definite NO’s,” they put the last five blacks in the jury pool on top and ranked them in case “it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors.

Foster’s lawyers fought in vain to get access to these notes in 1987. It was not until 2006 that the notes were finally released.

Historically the Supreme Court has operated under a presumption that state officials in death penalty cases operate in a color-blind manner. The burden is on the defendant to overcome this presumption by proving intent. The court has rarely failed to affirm convictions of blacks in death penalty cases despite statistics showing glaring racial disparities.

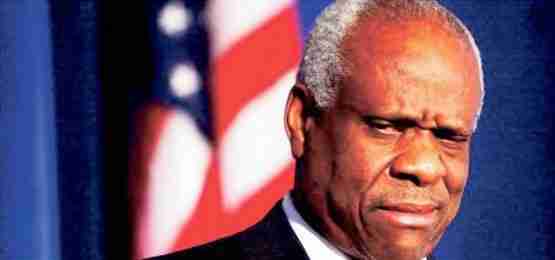

But in this case, in the words of Stephen Bright, president and senior counsel for the Southern Center for Human Rights and Foster’s attorney, there was an “arsenal of smoking guns.” The focus on race in the prosecution’s file plainly demonstrates a concerted effort to keep black prospective jurors off the jury,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the 7-1 verdict. Only Justice Clarence Thomas, the only black justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, dissented.

This was an incredible victory. The evidence was compelling. As Justice Elena Kagan stated, what it really was, was they wanted to get the black people off the jury. But there is social dimension to this. David Elliot of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty has stated there has been a subtle shift in public opinion about the death penalty. While most Americans staunchly support the death penalty there is increasing awareness that it is imposed too often unjustly

The Supreme Court is getting the message. The winds of change are starting to blow from a very surprising place.

Donald Jones, Esq. is professor of Law at University of Miami. He can be reached at theumprof@aol.com

No Comment