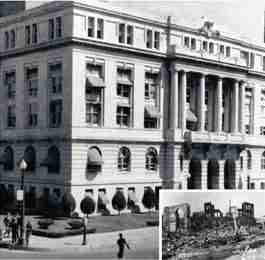

At the end of the day, June 1, 1921, this is what remained of Black Wall Street. Lost forever were over 600 successful businesses, including 21 churches.

By DAPHNE TAYLOR

Part III

In 2016, an important historical document came to light. It was a ten-page manuscript written by a Negro lawyer who survived the 1921 Tulsa Massacre of Black Wall Street. Before then, there had never been a first-hand, written, eyewitness account of the massacre that burned Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma to the ground on May 31 and June 1, 1921. It was a poignant, descriptive, manuscript, providing the most chilling details regarding the horrific accounts of the Memorial Day holiday-week massacre.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low.I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top,” wrote Buck Colbert Franklin, a lawyer, who was born in 1879 and died in 1960.

The Oklahoma lawyer, father of famed African-American historian John Hope Franklin (1915-2009), was describing the attack by hundreds of whites on the thriving black neighborhood known as Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.”

Franklin writes that he left his law office, locked the door, and went down to the foot of the steps.

“The sidewalks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top,” he continued. “I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?”

Franklin’s manuscript now resides among the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. The previously unknown document was found in 2015, purchased from a private seller by a group of Tulsans and donated to the museum with the support of the Franklin family.

The only other recent account has been given by Black Wall Street’s only survivor, 102-year old Dr. Olivia Hooker, who was last known to reside in White Plains, New York. Hooker told her accounts of the massacre in 2015 to the Wall Street Journal when she was 100 years old. In that interview, Hooker refused to identify the Tulsa Race Riots of 1921 as a “riot.” She says that what she survived at age six, was much more sinister than that.

“I refuse to call it a riot, because it was really Whites decided to burn down the homes of 10,000 people. That was not a riot. It was planned desecration. We were just small children and my family had not told me about prejudice and hate and things like that. I thought everything in the preamble to the Constitution referred to me. I didn’t find out until this terrible night.”

Hooker went on to describe her family’s plight. “When the mobs came in, they had those pine knots all lighted up and they set things on fire.

My mother refused to run because she was busy putting water on the house to keep it from burning. And so, she put the children under the big oak table. You know they had those great big tables, in those days, with little nooks under them. So, we were under the table when the mobs came in. And my mother had said, ‘Well, we have to eat no matter what.’ So she was cooking. And they got so angry that she had–what she called– her three cornered pots on the stove and she had something different in each pot. So they took those out and threw them in the backyard. And then they took the beautiful brown biscuits out of the oven and took them out and smashed them in the mud. So we’re under the table looking at all of this.

“So it was very devastating to me because the only non-Black people that I ever saw were people who wanted to sell my father things for his store. And they brought presents for the children and listened to my sister play the piano. You know how salesmen behave. I thought that was the way all non-Black people behaved,” said Hooker, born February 12, 1915. She was the first African American woman to have entered the U.S. Coast Guard, which she did in February 1945.

A retired psychologist and professor, she was one of only five African American females to first enlist in the SPAR (Semper Paratus Always Ready) program. a member of the United States Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, during World War II.

She earned the Yeoman, Second Class rank during her service, and she served in the Coast Guard until her unit disbanded in mid-1946. Later she went onto to be a psychologist and a professor at Fordham University. Hooker applied to the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) of the U.S. Navy, but was rejected due to her ethnicity. She disputed the rejection due to a technicality and Hooker was accepted.

She earned her Bachelor of Arts in 1937 from Ohio State University, where she joined the Delta Sigma Theta sorority and she advocated for African American women to be admitted to the navy. She received her Masters ten years later in 1947 from the Teachers College of Columbia University. In 1961, she received her PhD in psychology from the University of Rochester. Hooker was a founder of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission in hopes of demanding reparations for the riot’s survivors.

In 2003, she was among survivors of the riot to file an unsuccessful federal lawsuit seeking reparations.

There is also a stunning South Florida connection to the Black Wall Street Massacre. Andrew J. (AJ) Smitherman, born in 1883 and died in 1961, is the great grandfather of noted Florida businessman and entrepreneur Terence “Coach” Smith. His great grandfather survived the massacre and

afterwards moved North to rebuild his newspaper business. Smith, who is President and CEO of Legacy Commercial Capital, said his business practices and personal philosophies today embody those of his great grandfather.

Smitherman advocated “self-help” and “social uplift” for black Oklahomans. He convinced Tulsa to create a black voting precinct where he was appointed the inspector of elections. Smitherman also cooperated with various governors of Oklahoma on a number of occasions to prevent lynching and rioting.

In 1917, when a white mob burned at least twenty African American homes in Dewey, Oklahoma, Smitherman reported the episode directly to Gov. R.L. Williams, resulting in the arrest of thirty-six white perpetrators, including the mayor of Dewey.

Smitherman learned the newspaper business working for the weekly Muskogee Scimitar. In 1911, he started his own newspaper, the Muskogee Star, and in 1913 he moved to Tulsa and launched the Daily Tulsa Star.

Smitherman edited and published the paper at his plant until June 1, 1921, when white rioters in Tulsa destroyed the paper in retaliation for his political activism. His home and business were burned to the ground and mob rule forced him, his wife, and their five children to flee to Massachusetts. Oklahoma prosecutors attempted to have Smitherman extradited to stand trial for the crime of incitement to riot, but Massachusetts never cooperated with extradition efforts. A year later, Oklahoma Klansmen cut off the ear of a relative of Smitherman’s in an act of racial intimidatio.

Under such circumstances, he sold his remaining business interests in Oklahoma to Theodore Baughman, who started the Oklahoma Eagle. Smitherman never again returned to the Sooner state.

“My great-grandfather stood up against them. He stood up against the Klan. He was the only person they had the audacity to indict–saying he started the Tulsa riots!” said Terence “Coach” Smith, in an interview from his home in Kissimmee, Florida. “They said it was his fault and they wanted him to come back to Oklahoma so they could kill him! He never went back.”

Terence Smith’s relatives tell him he gets his passion for justice and his will to succeed from his great grandfather. “They say he was very strict,” said Smith, who is known as “Coach” for his business acumen and coaching style in business. “And I’m very detailed, too. My spirit of entrepreneurship, I get from him.”

Smith says he has developed his life’s philosophy from his courageous great grandfather. “You have to stand up for what’s right, even if it costs you your life. In my business, I often ask myself, ‘What would my great-grandfather do?’ Because of what he did — that is what drives me to do what I do today!” Smith proudly stated.

No Comment