MIDDLETOWN, N.J. (AP) – Joe Manzi was working at St. Leo the Great Church, where he’s an administrator, when he spotted a man and woman wandering along the wooded hillside next to the parish center.

This was shortly before Memorial Day a few years back, and they were carrying American flags. He wondered what they could be doing. “We’re here for the cemetery,” one told him.

“What cemetery?” Manzi said.

Turns out, there was a 2-acre, 19thcentury cemetery beneath the thicket of overgrowth. And it wasn’t just any burial ground. This was specifically for African Americans – among them freed slaves and Civil War soldiers. It was an important place, lost to time.

“I was totally amazed, since none of the church records references that this cemetery was here,” Manzi said.

A massive cleanup made historic Cedar View Cemetery presentable in 2015, but there is more to be done, and a new push is underway.

Historical records show that on Nov. 14, 1850, a prosperous Monmouth County farmer named John Crawford sold the land for the cemetery to 14 black men. Crawford, a former slave owner, indicated that there would be 24 equal lots and he made $60 off the deal.

“It’s one of several intact African American cemeteries in Monmouth County, but not all of them can be found,” said Joe Grabas, who sits on the Monmouth County Historical Commission. “The fact that we have this is important. There was a large African American population in Monmouth County from the very beginning – originally brought here as slaves but eventually freed.”

In that era, such men and women would have ended up buried in the graveyard associated with their church. This was different.

“These people in that graveyard actually own the land,” Grabas said. “They (their descendants) still own it today. At a time when not many African Americans owned land period, the fact that they could buy some land for their final resting place is significant.”

Graves in the cemetery date from the early 1850s to 1942. According to a report by Edward Raser of the Genealogical Society of New Jersey, the last known survey of the cemetery took place in 1979 and noted 45 stones. Then nature took over. When Manzi first explored the property five years ago, just one gravestone was visible, and it was so engulfed in weeds he nearly tripped over it.

“It took us literally a half hour to transverse 50 feet,” he said. “You couldn’t see anything.”

RACIAL COMMENTARY

Why had the cemetery disappeared from consciousness? Joelle Zabotka, a professor of social work at Monmouth University and a member of St. Leo the Great Church, dove into researching the site and could not find it on old maps. Only the small cemetery across Hurley’s Lane – one for whites –turned up on them.

“That tiny cemetery is shown on maps of the time and yet (Cedar View) is never shown even though it’s significantly bigger at 2 acres,” Zabotka said. “Is that a racial commentary of the time? I take it that way.”

So obscured was the land’s origin that Middletown’s tax records erroneously attributed the property to the church.

Zabotka led the group of more than 100 volunteers, including Boy Scout troops and Monmouth University students, who spruced up the site and pieced together its history in 2015. They found the Red Bank Register’s obituary of Charles Reeves, who was buried there in 1900 at age 80.

Owned by a Holmdel resident named David Williamson until he was freed at age 25, Reeves went on to work as a paid farmhand and “became one of the best-known colored men in Middletown,” the obituary noted. He did well enough to buy a horse, enabling him and his wife to ride to church in Red Bank from their Lincroft home each Sunday – instead of walking.

Tinton Falls native Rob Shomo’s great grandfather is buried in Cedar View. William H. Shomo was a farmer who later drove delivery wagons.

“We grew up 5 miles from the cemetery and never knew anything about it,” Rob Shomo said. “This is an important place for a lot of us because it’s about as far back as we can go (tracing family history). It’s a piece of African American history in Monmouth County that got left out.”

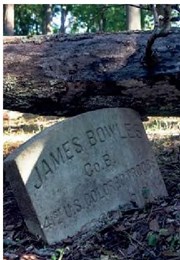

Manzi said there are 12 Civil War and World War I veterans buried in Cedar View. One of them is James Bowles, whose clearly marked headstone is half-buried, hammered into the earth by a fallen tree. Bowles lived from 1832 to 1916 and served with the 41st U.S. Colored Troops, which fought in some of the Civil War’s decisive battles, including the siege of Petersburg and Appomattox Court House. The 41st was on hand when Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered.

LAND, LEGACY CURATORS NEEDED

Many of the gravestones are in bad shape – worn illegible, broken or uprooted. Manzi thinks more than 200 people are buried at Cedar View.

“We believe there are a lot of graves of people who were buried without headstones, or graves that were wood and disintegrated over the years,” he said.

One of the goals moving forward is to find someone who can use ground-penetrating radar to locate unmarked graves. Another is to put up a perimeter fence, giving the grounds more prominence. A wooden walkway from Hurley’s Lane and two signs, including a map, went up in 2015.

“There needs to be a respect for the people buried here,” Manzi said. “The troops who were buried here were forgotten.”

Monmouth University students are doing a site cleanup Oct. 26 and others are welcome to help. Ultimately, though, caring for Cedar View requires regular attention. Grabas would like to see a “Friends Of” society established to curate the land and its legacy.

“It can easily go away again,” he said. “If an effort is put forth by the community, there’s no reason it can’t be saved for future generations.”

No Comment